FEATURING...

by Tom Larwin (San Diego Metropolitan Transit Development Board) &

Cliff Henke (METRO Magazine)

On Examples of Low-Cost Light Rail Solutions In North America:

"The challenge for the next 15 to 20 years will be a financial one: how to keep LRT affordable"

The light rail renaissance in North America, which began nearly 20 years ago, had modest beginnings. As such, these cities could provide models for others in both developed and now developing nations looking to improve their rail urban transport infrastructures.

The experiences of cities that will be discussed in this paper highlight Calgary, Edmonton and San Diego, the first cities to resurrect light rail on the continent. Other cities' experiences for keeping the costs of new system down will be included, such as St. Louis and Denver. In addition, the presentation will include a list of "best practices" for other cities gleaned from the North American experiences. Where possible, these will be compared with the characteristics of pending or anticipated projects in the U.K. and elsewhere in Europe.This text was published in 1997 for the first time. Nevertheless Light Rail Atlas still considered it as an important topic, since current light rail projects in America and Europe tend to be high-cost!

Thanks to the Metro Archives.

Editor of this internet-version: Light Rail Atlas

All photos: (C) RVDB/LRA, 1994-2000

San Diego's first line, here seen at the mexican boarder, is low-cost and a great success as well.full text:

On Examples of Low-Cost Light Rail Solutions In North America:

"The challenge for the next 15 to 20 years will be a financial one: how to keep LRT affordable"

by Tom Larwin & Cliff Henke

Introduction

Although modern light rail development has modest beginnings in North America, development has proceeded sufficiently to declare that a true renaissance of rail urban transport is well underway on the continent. Since the 1970s, no fewer than 11 U.S. cities have started to operate new LRT systems, while four others have modernized their older streetcar networks. Canada and Mexico each have two new systems while another city of each nation has upgraded and expanded older networks. Most impressively, most of this activity has occurred in just the past decade and a half.

Nor does this reawakening show any signs of abating soon. Indeed, virtually all these cities have serious plans to expand their systems, while at least as many other North American urban areas are in various stages of planning or construction of their own LRT schemes.

Thus, there is now a sufficient body of experience in North America to enable a characterization of LRT development on the continent, particularly in the western United States and Canada. This paper will discuss those "North American" characteristics in the form of "best practices."

Most of these ideas, though not all, will be discussed via examples drawn from the new California systems. (San Francisco's upgraded Muni system will thus be excluded.) This is in part due to the greater familiarity of the authors of these systems versus those of other North American cities. However, it is also due to the fact that the California cities were at the vanguard of the continent's LRT renaissance, and by virtue of going first, they laid the groundwork for others that followed.

While these techniques are by no means unique to North America, they serve to illustrate the high degree of collaboration among the continent's urban transport professionals and how cities developing later systems learned from experiences of those who built LRT projects before them.Best Practice #1: Use Other Systems' Best Ideas

These early (modern) LRT applications used various German and Swiss cities as models in designing its system. One noteworthy example is related to the type of vehicles employed. Calgary, Edmonton and San Diego initiated service with the Siemens Duewag U-2 car, representing an "off the shelf" piece of equipment that had operated for years in various European situations. Sacramento followed with procurement of a Siemens vehicle very similar to that used in San Diego. Both San Diego and Los Angeles have new car orders pending with this same manufacturer [cars are deliverd in the meantime; LRA]. San Diego's involves the manufacturer's later SD-100 design, the vehicle comparable to the one operating in Sacramento. These procurements will be discussed later in this paper.

The Los Angeles system includes high-level platforms, like these in Long Beach.Los Angeles incorporated other successes of San Diego's first line. Indeed, during the early 1980s, it was widely reported how then-Los Angeles County supervisor Kenneth Hahn admired the San Diego Trolley's development and operating characteristics. In particular, he was particularly impressed as to how San Diego used an existing freight railroad right-of-way, albeit a single-tracked one, as well as simple, barrier-free stations with self-service, "honor system" fare collection.

However, to accommodate the needs of handicapped riders, the design of the Los Angeles system includes high-level platforms and, thus, level boarding. California's other properties all utilize low-level platforms to enable wheelchair patrons to get onto the system. The San Diego system has employed a lift onboard the vehicle at one of the doors, while the Sacramento and Santa Clara systems have both used on-platform ramps or lifts in order to get the wheelchair patron to a level loading situation. These latter two properties are presently seriously considering low-floor LRVs for their next order of cars. The primary purpose for going to a low-floor vehicle would be to assist handicapped passengers, as well as to speed up normal boarding and unloading of passengers.

Hahn and other Los Angeles officials also knew there was an existing corridor in their service area that could be adapted to modern LRT service using design and operating techniques proven in San Diego. Not coincidentally, it was the last corridor served by the former interurban network in Los Angeles, the Pacific Electric route between Los Angeles and Long Beach. Hahn, whose constituency included the communities along this corridor, used his formidable political skills to reconstitute this service with modern LRV technology. The new service is called the Blue Line, the first line in a larger rail transit network that is to comprise 400-plus route-miles in Los Angeles County.

One other important facet of this L.A. project that was similar to the San Diego approach was the political and financial impetus. Both cities relied heavily on local leadership and financing to see their LRT experiments to fruition. In the case of L.A., Hahn and others successfully led a referendum in 1980, called Proposition A, to earmark part of the county sales tax for public transport, specifically for bus fare subsidies and a 100-mile rail network. Most of the latter was to be light rail.

Both cities' leaders were well aware that this important step allowed them to develop their schemes without dependence on federal government finance, which was at best an unreliable source of finance. Second, a dedicated local source of funding allowed system designers to work with a minimum of "meddling" by federal government rules. In fact, all but one line of Los Angeles' expanding rail network and much of other California cities' LRT systems are financed without significant central government contributions to this day.

San Jose integrated its light rail with the public space of downtown.

San Jose's LRT start was also built on the examples of others. In fact, both San Jose and Los Angeles borrowed from the ideas behind Toronto's successful system. In the case of San Jose, planners there were impressed with how Toronto integrated its network with the town plan, and how joint development schemes between the public transport agency and private real estate firms were used to make Toronto's system more relevant to residents' travel needs. San Jose also was impressed with Toronto's six-axle double-articulated vehicles, built by Canadian firm UTDC (later acquired by Bombardier).

On its heavy rail line, Los Angeles has borrowed another joint development idea used in Toronto (and other American cities), called "benefit assessment districts," a special property tax assessed on the appreciated value of property within a specific distance to rail stations. These special taxes comprise some 5% of funding of the $5.3 billion Red Line (the only line in the L.A. scheme to be metro).

Still another Toronto-inspired concept to be used in Los Angeles is the idea of applying specific technologies to a particular line in the network--even if this results in a multiplicity of technologies that are not standard to other parts of the system. However, it should be noted that this idea has been retracted somewhat recently. In 1995, the board of the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority voted to develop a so-called "L.A. Standard Car," which could be used on all LRT lines of the network. This vote reversed a decision calling for driverless cars on the recently opened Green Line, which was to be similar to Toronto's Scarborough RT project.

The idea exchanges continues to this day and, hopefully, well into the future. Like European nations, one of the benefits of having four new LRT systems within one state is the sharing of information and the combination of common interests.

A good example of these mutual benefits is the California Transit Association's Guideway Regulatory Subcommittee. This Subcommittee consists of representatives from all rail properties within the state, and provides a communication forum for regulatory and operating issues. By bringing rail transit operators together into a subcommittee, a more consistent and influential voice can be used to affect stateside and federal policy. The success of the combined approach has been well-demonstrated in the interaction with the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC). The Subcommittee was particularly effective in the development of General Order 143A, which pertains to light rail transit operations. There have been numerous other activities where the Subcommittee interacted with the CPUC staff or other state and federal entities.

Standardized traffic control devices have been approved by Caltrans and the California Traffic Control Devices Committee with coordinated input from the state's LRT operators. The current Federal Transit Administration (FTA) promulgation of safety and security guidelines is an example of another area where the operators combined to work together in unison with the CPUC to develop practical and consistent guidelines.

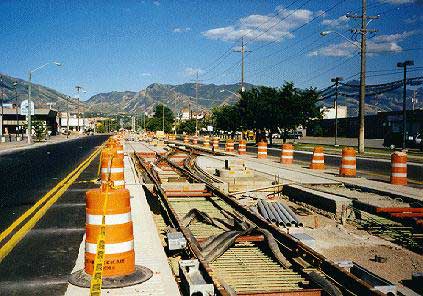

Salt Lake City: the Mainstreet section under construction during summer 1998.

Beyond the opportunities for information and intelligence sharing, this situation has produced opportunities for cost savings as well. This has been demonstrated in numerous ways through joint procurement activities.

San Diego and Los Angeles joined together on the procurement of concrete ties. San Diego and Santa Clara joined on the procurement of ticket vending machines. Sacramento and San Diego have shared significant intelligence with regard to experience with the Siemens light rail vehicle. Numerous opportunities will continue to present themselves for joint procurement in the future as these new systems mature and expand.

One such opportunity occurred with Denver's initial car procurements. Its purchase of 11 SD-100 LRVs was added to San Diego's order pending with Siemens (with another 6 ordered due to ridership increases). Further, the same strategy was just announced with Salt Lake City's initial segment, which is set to be operational in time for the 2002 Winter Olympics hosted by that city [already operational in 1999!; LRA].Best Practice #2: Develop the System Incrementally

The incremental approach helps minimize the effects of costly mistakes while providing valuable experience for future extensions and service upgrades. All four newer California properties have undergone extensions to their systems or significant enhancements. These ongoing expansion activities allow intelligent upgrades to design criteria and equipment performance specifications. For example, San Diego has refined its design criteria numerous times to reflect experience of a more complex operation handling many more passengers at key stations today as compared with 1981. Moreover, there have been improvements continuously added to each system, based upon operating experience, that work toward reducing the unit cost of maintenance and/or enhancing the operations of the system.

Again, the incremental nature of light rail transit demonstrates that the initial system can be opened and operated in a more simplistic fashion (e.g., with single track operation) and incrementally enhanced as time goes on. The four California experiences show many such cases of enhanced design: smaller, but more powerful traction power substations; improved street crossing panels of a pre-fabricated nature; improved traffic controls; reduced delay at grade crossings that are located at nearside stations; and improved ticket vending machines.

These operating efficiencies and upgrades are especially important since new extensions are generally being built at higher costs. As demonstrated in Los Angeles and San Diego especially, new extensions are tending to be developed with more grade separations than earlier portions of the system. Other capital-intensive ideas that are being incorporated into these new extensions include: "smart" ticket vending machines that will accept credit/debit cards, the possibility of turnkey construction, the addition of bike racks on vehicles, and increased attention to art.

Another advantage to incremental development is that the experience gained on the initial segments of the system becomes critical as the inherent nature of maturing systems increases operational complexities. As the new systems mature, increasing operating dollars are needed for upkeep and preventative maintenance due to aging of fixed facilities and vehicles. In addition, as ridership increases and additional services are added, operational flexibility in the design of trackwork becomes increasingly critical to providing high-speed and reliable operations. Furthermore, platform widths may have to be expanded, additional ticket vending machines may have to be added, additional crossover tracks may be required and, in some cases, pocket tracks or third tracks may needed at outlying locations. As with most new North American operations, San Diego's 15 years of development history show a range of incrementally developed enhancements and extensions following the opening of its initial segment. Enhancements have included: double tracking the initial South Line, adding a grade separation to an operating line, and adding a station to an operating line. Extensions to the San Diego Trolley have included: 7.2 km (4.5 miles) in 1986, 17.6 km (11 miles) in 1989, 2.4 km (1.5 miles) in 1990, 1.6 km (1 mile) in 1992, 5.6 km (3.5 miles) in 1995, and 5.6 km (3.5 miles) just recently in June 1996. The next San Diego Trolley extension is due to open in late 1997.

Other cities have followed a similar pattern:

=In Sacramento, a 3.7 km (2.3 mile) extension is Mather Field is scheduled to open in 1998 [and it did!; LRA]. In addition, three other extensions are scheduled to open by the year 2002: one to the east, one to the south, and a short extension to serve the AMTRAK station in downtown.

=In San Jose, the 20 km (12.4 mile) Tasman Corridor project is scheduled to be phased in and completed by the year 2000.

=In Los Angeles, the 22 km (13.7 mile) Blue Line extension to Pasadena is to be constructed largely at-grade and in railroad right-of-way; it is scheduled to be complete by the year 2002.

=In Denver, an 8.7 mile extension to the southwest of city center is nearing the start of construction, with an expected opening early in the next decade.

=In St. Louis, the region's voters approved by a wide margin a plan to extend the system 40 km (25 miles) to the east in nearby Illinois suburbs. It is scheduled to open in 2002.

=In Portland, an initial 18.5 km (11.5 mile) segment of the Westside Corridor is scheduled to open next year, and another 10 km (6 mile) segment of the Corridor will open a year later [now in 2000 both segments are finished; LRA].Another trend with the new extensions, borrowing ideas somewhat from Toronto, is to place more emphasis on land use integration, joint development activities, and transit-orientated development. While this might mean more capital costs up-front, such transportation-land use coordination becomes a "win-win" for transit and the community in the longer run. Increased potential transit trips are generated for the transit system, while the coordinated land use planning promotes walking and non-automobile use and higher-quality neighborhoods.

For example, in San Diego, the city has adopted a transit orientated development (TOD) policy that has been utilized for an integrated LRT-land use plan implemented as part of the Mission Valley project under construction. The stations located as part of this new extension in San Diego are either at already existing major activity centers or at those that are being expanded or newly designed as part of the city's TOD policy.

Comparable transportation-land use design efforts characterize the South Corridor planning for the Sacramento system expansion. Similarly, the Santa Clara system is showing the fruits of working with various cities in its jurisdiction to increase housing intensity around stations and implement joint developments such as child care facilities at stations.

From a transportation-land use point of view, LRT's linkage with major activity centers have become critical to a system's ridership. Several LRT systems have designed either their initial operating segments or subsequent extensions to serve major activity centers, such as the central business district (CBD), sports facilities or shopping centers. In St. Louis, for example, virtually every other station on its Metro Link line serves such a center. Recently, the system was extended to interconnect the city's international airport.

Every other system serves the city's CBD. In the case of Los Angeles, the initial Blue Line operation also connected with another major central business district in the city of long Beach. Similarly, San Diego's North-South Line connects not only the San Diego central business district but also has its terminal station within walking distance of the Tijuana, Mexico central business district. As the new extensions get developed, all of the new systems will have at least two corridors approaching the CBD. A connection with AMTRAK services is also a prime feature of the systems in Los Angeles, Baltimore, San Diego, and Santa Clara; such a connection will be completed in Sacramento within the next few years. Major convention facilities are directly served by the Los Angeles, San Diego, St. Louis and Santa Clara systems as well. San Diego's new Mission Valley extension will serve the stadium that hosts major sporting events.

The point here is that an important factor in the ridership success of these systems is the linkage of each new segment of service to major activity centers; this strategy can include a variety of attractions and not just be the region's central area.

Sacramento: westbound train at Butterfield;

At the background the Mather Field Road extension, under construction, which opened for service on 6 September 1998.Another new wrinkle that is being added to the extension projects is the provision of funding for art. In Santa Clara, an integrated art program will be provided as part of the Tasman Corridor project at a cost of $1.2 million (out of a total project cost of $530 million). In Los Angeles, one half percent of the total project budget is reserved for public art as part of its agency's policy. In Sacramento, small art projects have incorporated into each of its stations. In St. Louis, special art was incorporated into stations with the help of local arts organizations. San Diego, on the other hand, has not included art to any significant degree until its most recent extension to Old Town. As part of that project, an artist was employed to develop a positive experience in a pedestrian passageway that is located in its major terminal station.

Best Practice #3: Begin Public Involvement Early (And Keep It Going)

Characteristic of most new LRT systems in the U.S. is that they enjoyed strong local support. This is especially true of all of the new systems that were built in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Opening of the initial San Diego Trolley system in 1981 represents a good example of how local support is mustered. The initial push for light rail in San Diego came about through the efforts of California State Senator James R. Mills in the early and mid 1970s. Senator Mills' legislation helped lead to a constitutional amendment to permit state highway account monies to be used for guideway construction. In addition, he authored legislation that created the San Diego Metropolitan Transit Development Board (MTDB). The primary purpose of MTDB was to have the necessary powers to create a guideway transit system.

However, these efforts at the state level merely opened the door for the development of a necessary coalition of local leadership to confirm the mode, select the corridor and manage the project budget and schedule. MTDB's eight-person board at the time became very united behind implementation of the LRT project. Its leadership included the Mayor of San Diego at the time (and current Governor of California), Pete Wilson, and a subsequent Mayor, Maureen O'Conner. Their leadership was crystallized once an affordable railroad right-of-way was negotiated and the concept of a low-cost, affordable rail transit system was found to be feasible for San Diego. This concept of low cost also became a key ingredient in convincing heretofore reluctant, conservative business leaders to get behind the project. The fact that the project could be built with existing state and local resources was seemingly a clincher.

Another lesson from San Diego was the multiplicity of objectives that were to be served by the LRT project. To ask San Diego's leaders in 1978 why they believed the project was feasible would have led to a variety of answers with regard to the project's benefits:=Relief to an overloaded existing bus route in a major transportation corridor;

=Relief to traffic congestion;

=Improvement of air quality;

=More efficient energy resource utilization;

=Revitalization of central business district redevelopment efforts; and

=Improved transportation service to "captive" travelers in the corridor.The LRT project opened in July 1981 and has enjoyed continuing ridership increases and a relatively high farebox recovery rate, leading MTD Board members to approve numerous extensions to the existing line as outlined earlier. Most significantly, in 1987, the residents of San Diego County voted to tax themselves for future transportation projects, and the San Diego Trolley was widely considered to be one of the most significant reasons for voter support. Also significantly, while the initial project in San Diego relied upon local and state funding, its practical operating features and successful start provided the impetus for federal funding for the East Line extension, which opened in 1989.

St. Louis perhaps raised the art of corporate and public involvement behind LRT development to a new level in the U.S. Outside of the Bi-State Development Agency, the St. Louis regional transit agency, few people in the transit industry believed that the city would get its system. Indeed, there were many rival cities competing for a limited pool of central government funds, which then represented the lion's share of capital finance for urban transport. Moreover, St. Louis applied for such monies at a time when the Reagan administration had a stated budget policy of no funding for new rail systems. To underscore that city's slim chances further, Bi-State officials proposed that its local contribution to the project's cost, which by federal law is supposed to be at least 20% of the total, would largely be donated land consisting primarily of disused railroad right-of-way. This was an unprecedented proposal, further heightening skepticism among already skeptical federal and industry officials.

Nonetheless, unified congressional delegations from the states of Missouri and Illinois, many of whom held powerful legislative leadership positions, succeeded in persuading their colleagues to appropriate money for the LRT line. Surmounting this hurdle, however, was to be only one of many Bi-State staff and its local supporters had to overcome before their new LRT line saw revenue service. Again, Bi-State had no significant local financial resources. However, the agency's larger mission of local economic redevelopment (it is not just a transport authority) gave it access to public and private leaders and a perception not traditionally enjoyed by urban transport bureaucracies. (Admittedly, all urban transit systems play these development roles; the St. Louis agency's economic mission was simply more understood than in most metropolitan areas.)

As the St. Louis project came closer to opening day, Bi-State formed three innovative public-private partnerships that helped to increase ridership beyond even the most optimistic projections. First, it solicited corporate and private sponsorships to help raise money for a public relations and advertising campaign as well as help fund art and other amenities in various stations of the system. Secondly, it forged a strong relationship with arts organizations to ensure that these public places became attractive and feel as if they were part of the local communities. Finally, the agency began a "Transit Ambassadors" program with the local grass-roots advocacy group Citizens for Modern Transit, which helped to explain the system during the crucial early weeks of the new line's opening. Bi-State staff, including those not typically assigned to these roles, were also enlisted as "ambassadors." This program of volunteers and temporary agency staff help served as a critical passenger information service that helped boost ridership and customer service even further.

Bi-State staff credit these programs as well as the route alignment, which serves virtually every major tourist attraction and entertainment facility in the region, for the line's success beyond expectations. Moreover, they credit these programs for the recent passage of a local sales tax dedicated for LRT expansion, which in a 1995 referendum carried by a two-to-one margin.Best Practice #4: Use Proven Technology

As mentioned earlier, a number of cities have made cost-effective railcar procurements based upon use of proven technology. However, costs for civil works are often far greater than the LRV procurements for many systems. Based on a cost per rider, for example, the three of the four most expensive North American systems,the Los Angeles Blue Line, Buffalo and Baltimore,use high-boarding, metro-style platforms, extensive grade separation and even run partially in tunnels. Baltimore's order of LRVs also incorporates AC propulsion, which is more expensive than DC traction on an initial purchase price basis but will likely experience lower operating costs and therefore lower life-cycle costs. All these features are more of a testament to LRT's great flexibility of application than to performance and productivity characteristics.

Such flexibility of even proven LRT technology often produces considerable capital cost savings. The most notable example is the use of existing freight railroad rights-of-way mentioned earlier. Another example is the use of low-floor vehicles in North America, long a practice in Europe. Thanks to federal accessibility requirements of the Americans With Disabilities Act and earlier laws, transit systems were faced with expensive construction of lifts, ramps and high boarding platforms to accommodate wheelchair-using riders. With low-floor LRVs, however, the need for such costly civil works to accommodate those with special needs is greatly reduced. Portland's new Westside Corridor extension will be the first North American system to use low-floor LRVs in revenue service.

As mentioned above, system upgrades subsequent to initial segments tend to be more complicated with more amenities, further driving up fixed costs. Perhaps most egregious of these projects is in Los Angeles with the decision to standardize future LRV procurements. Siemens Mass Transit Division will soon begin delivering the first of 54 "L.A. Standard Cars" to the MTA. These cars employ technologies from defense and aerospace industries as well as other locally specified features in order to create jobs in Southern California. They are also equipped with onboard controls to enable a quick upgrade to fully driverless operation.

In general, however, most North American systems fall in the low to middle area of the price range for new LRT systems. Most systems began modestly, with proven, off-the-shelf vehicle technology and use of existing railroad rights-of-way or even street running in some cases.The earliest modern systems in North America, Edmonton, Calgary and San Diego, all relied primarily upon the same light rail vehicle (from Siemens Duewag, now the Siemens Mass Transit Division) and operation utilizing existing railroad rights-of-way and, to a lesser extent, street rights-of-way. These early examples paved a way for application of a modern, improved rail transit technology in combination with a more productive use of existing right-of-way opportunities. Thus, significant cost savings were achieved with the use of these available, linear rights-of-way and low-cost ( and in some cases, no-cost) situations. Furthermore, the use of LRV technology with a proven record of performance in Europe provided these three cities with low-risk entry into rail transit service. The knowledge and experience gained in Europe, and the trial and error with the particular LRV used, allowed Calgary, Edmonton and San Diego to minimize disruption of service with highly reliable vehicles. Another gain is that troubleshooting is simplified when problems do occur. In San Diego's case, the initial fleet size of 14 vehicles was able to provide reliable, 20-minute headway service on a 26-km (16-mile) route for its first two years of operation. Two- and three-car trains were utilized during the weekdays, so spares were essentially nonexistent. The bottom line from these early experiences in North America is that the combination of a low-cost rail transit project with low-risk technology produces public confidence. The true test of this confidence is in the ridership growth of all three systems that occurred during their initial operation, and still exists to this day.

In fact, virtually all of the LRVs used in the U.S. and Canada are six-axle, articulated, double-ended. Their seating capacity ranges from 60 in Sacramento to 76 for two types of Los Angeles cars. The manufacturers vary (Duewag U2 or SD-100 models, ABB, Kinki-Sharyo, Bombardier and Sumitomo); however, where differences exist, those technologies chosen were unmistakably similar.Summary and Conclusion

Eighteen years since the opening of Edmonton's LRT system have shown North America to be a leader in light rail transit development. The four new systems in California,Los Angeles, Sacramento, San Diego, and Santa Clara County,have each been designed in their own unique fashion, yet they share many common characteristics. In addition, much can be learned from the experiences of this development history. Further, these lessons can be applied to future LRT system development.

The range of right-of-way conditions in which LRT operates in North American properties demonstrates this inherent flexibility, but it also shows how medium-capacity rail transit can be developed at a relatively low cost. This flexibility has been further demonstrated by the continuing incremental extension of LRT service to serve additional transportation corridors and activity centers.

The light rail transit systems throughout North America, but especially in California, continue to grow in size and in ridership. There is continuing pressure to expand the systems and yet keep a lid on operating cost increases. The challenge for the next 15 to 20 years will be a financial one: how to keep LRT affordable, both to construct as well as to operate, as these systems continue to mature. Certainly, a foundation of knowledge and experience is now in place to satisfactorily meet these challenges.Acknowledgments

The authors expresses their appreciation the following individuals for providing, data, information, and opinions used to prepare this paper: Mr. Peter M. Cipolla, General Manager, Santa Clara County Transportation Agency; Mr. Joe Marie, Director of Sales and Marketing, Siemens Transportation Systems Mass Transit Division; Mr. Thomas Sehr, General Manager of Operations, Bi-State Development Agency; Ms. Pilka Robinson, General Manager, Sacramento Regional Transit District; and Mr. Tom Carmichael, Facilities Engineering Manager, Los Angeles Metropolitan Transportation Authority. References

1. Cameron Beach, "Sacramento Regional Transit's Light Rail: Approaching Middle Age," Transportation Research Board, Seventh National Conference on LRT, Volume 1, 1996. pp. 3-14

2. Robert L. Bertini, Jan L. Botha, and K. Odila Nielsen, "Light Rail Transit Implementation Perspectives for the Future: Lessons Learned in Silicon Valley," Transportation Research Board, Seventh National Conference on LRT, Volume 1, 1996. pp 3-14.

3. California Public Utilities Commission, General Order 143A, Safety Rules and Regulations Governing Light Rail Transit, adopted May 8, 1991.

4. Robert T. Dunphy, "Review of Recent American Light Rail Experiences," Transportation Research Board, Seventh National Conference on LRT, Volume 1,1996, pp 104-113.

5. Cliff Henke, "Why U.S. LRT Outlook Remains Good," METRO Magazine, Mar./Apr. 1996, pp. 28-34.

6. Thomas F. Larwin and Langley C. Powell, "Light Rail Transit in San Diego: The Past as Prelude to the Future," Transportation Research Board Record 1361,1992, pp. 31-38.

7. Thomas F. Larwin, "LRT in San Diego: A Look Back, A Look Forward," Institute of Transportation Engineers Annual Meeting Compendium, Oct. 1994.

8. Thomas F. Larwin, "A Retrospective of Lessons Learned from New California LRT Operations," Third International Conference on Light Rail, International Public Transport Union (UITP), San Jose, CA, September 1996.

9. Lenny Levine, "L.A., Transit Lab of the World, Carves A Niche In Region's Psyche," METRO Magazine, Sept./Oct. 1993, pp. 34-58.

10. Paul O'Brien, "Standardization: Historic Perspectives on Modern California Light Rail Transit Systems," Transportation Research Board, Seventh National Conference on LRT, Volume 1,1996, pp. 31 11. Neil Peterson, "Standardization: The Los Angeles Experience in Divergent Technologies," Transportation Research Board, Seventh National Conference on LRT, Volume 1, 1996, p. 140. 12. John W. Schumann and Suzanne R. Tidrick, "Status of North American Light Rail Transit Systems: 1995 Update," Transportation Research Board, Seventh National Conference on LRT, Volume 1,1996, pp 3-14.

Mail LRA your questions and comments.